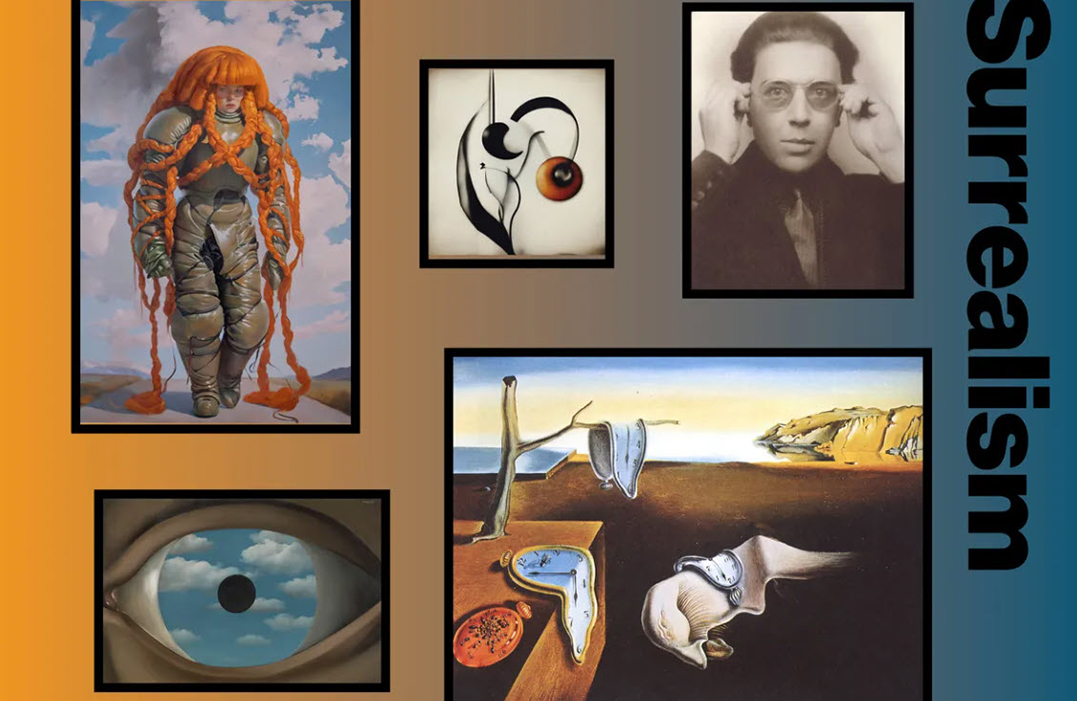

“This is not a pipe”: Why do AI Images Look Surreal?

By now you’re probably familiar with text-to-image programs like DALL-E, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion, so you have a sense for the aesthetics of the images they produce: glitchy, plastic, uncanny. Even the “realistic” examples feel just a little surreal. There are practical reasons for this—and not all of them are technical.

Surrealists have long been fascinated by the slippery relationship between objects and the words we use to represent them. It’s the central idea behind one of the movement’s signature images, René Magritte’s 1929 painting The Treachery of Images. Famously, the artwork features just two basic components: a picture of a pipe and an accompanying caption that reads, “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (“This is not a pipe”). Magritte’s gesture was both revolutionary and remarkably banal. Its wit works because we’re so used to negotiating the gap between signifier and signified that we almost forget the gap exists at all. But AI models, which “learn” through analyzing visual and textual data, are not so adept.

“Ingesting many different images of a ‘chair’ can allow a model to develop some kind of understanding of what a ‘chair’ might look like in different scenarios, but models don’t comprehend what a chair is as we might do,” explains the British-born, Berlin-based artist and theorist Mat Dryhurst. “In the course of generating the image, the system is trying to approximate something very new based purely on pixel data and concepts pieced together from that data.”

Dryhurst and his partner in life and art, the American composer and artist Holly Herndon, are among those driving the discourse at the edge of AI art. Their own work isn’t very surreal, but it is abstract, often because what they make is systems that make art. The duo has produced algorithm-aided electronic music, developed a program that allows singers to perform using a deepfake version of Herndon’s voice (they demonstrated it in a TED Talk, then used it to cover Dolly Parton’s “Jolene”), and helped launch a website that enables artists to remove their work from datasets used to train AI models. For the 2024 Whitney Biennial, they created a free app that produces ultra-exaggerated, “hairy mutant” pictures of Herndon. The goal is to produce enough of these user-generated pictures so that in the future, when commercialized text-to-image models create a portrait of her, the results will hew to the likeness she chose, not the aggregate one combed from the internet.

Herndon and Dryhurst’s Whitney contribution explores the fluidity of consent, identity, and intellectual property in the Web 3.0 world. But the project also points to one of the defining aspects of AI-produced images. Because these programs are synthesizing pictures from millions of jpegs scraped from online, the results are, by definition, amalgamated—and amalgamated images look unnatural. They’re like those composite faces used to illustrate the “averageness” theory of attractiveness. In the end, they all look like Jesus: a little familiar, kind of hot, completely unmemorable (also, far too often, inexplicably white). With all notable characteristics blurred to the median, their beauty is, paradoxically, the average kind.

The German artist Hito Steyerl uses the term “mean images” to describe these AI-generated composites. “They are after-images, burnt into screens and retinas long after their source has been erased,” she wrote in a New Left Review essay last year. “They perform a psychoanalysis without either psyche or analysis for an age of automation in which production is augmented by wholesale fabrication.” For Steyerl, “mean images are social dreams without sleep, processing society’s irrational functions to their logical conclusions. They are documentary expressions of society’s views of itself, seized through the chaotic capture and large-scale kidnapping of data.”

BY TAYLOR DAFOE